East African Charcoal ‘Grey markets’ criminality

By Murani Hillary

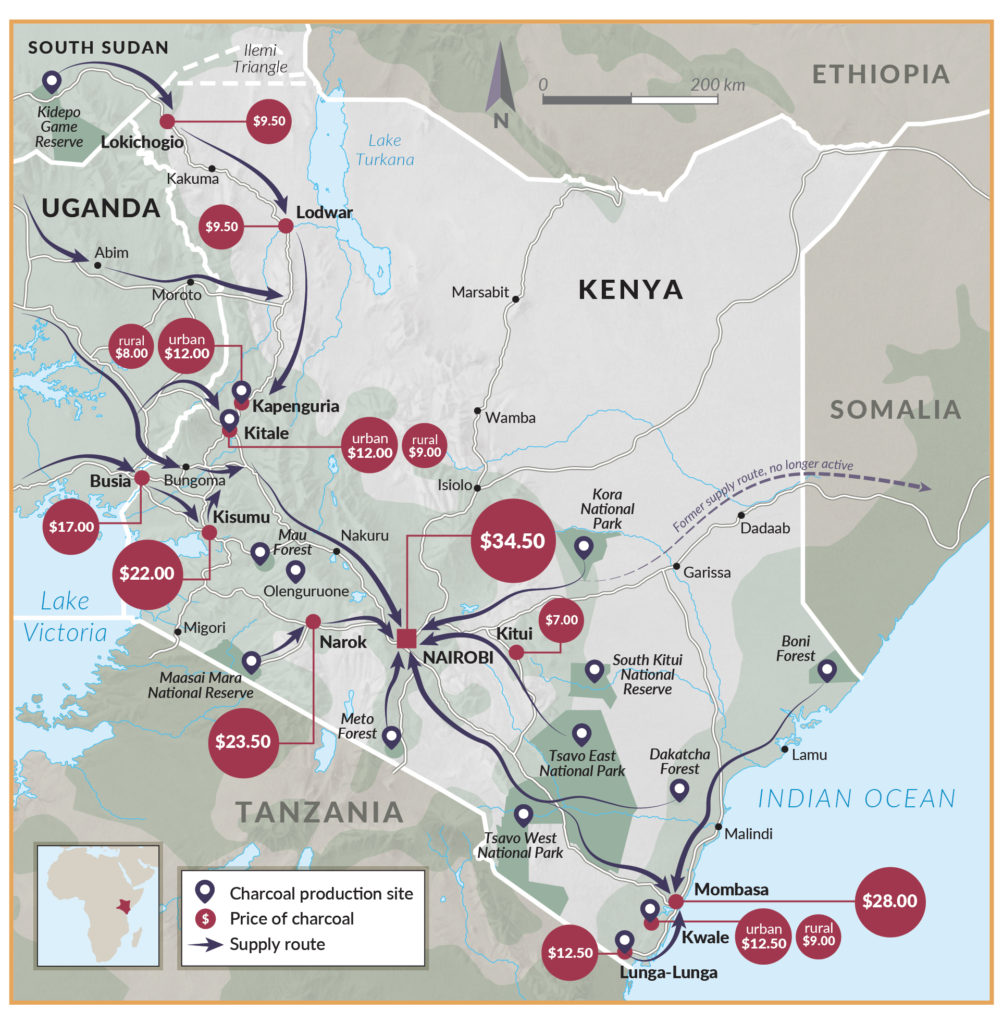

Despite the national moratorium on charcoal production, the charcoal market in Nairobi-Kenya’s Capital, continues to turn a significant annual profit, worth millions of dollars. Rapid urbanization across East Africa is contributing to rising demand for energy.

The incentive to produce charcoal – by illicit as well as legal means – is therefore set to increase in the future since most of Kenya’s population do not have access to clean cooking fuels and instead rely on fuels such as charcoal for their daily needs. The Global Initiative (GI) has observed.

The aim of this moratorium was to conserve the country’s forests. However, research by GI-TOC found out that it has had unintended consequences. According to charcoal producers, the moratorium damaged the livelihoods of those in producing areas.

‘The ban came like death; there was no forewarning,’ says Tsingwa Nduria, chairperson of the 2000-member charcoal producers’ association in Msambweni, on Kenya’s south-east coast.

Despite the disruption, the trade has continued as a lucrative grey market, where corruption and criminality now exist along the value chain. According to Global Initiative Transnational Organized Crime Investigations- GI-TOC, James*, 50, a matatu driver in Embakasi, in the south-east of Nairobi has been transporting charcoal illegally past corrupt police officers.

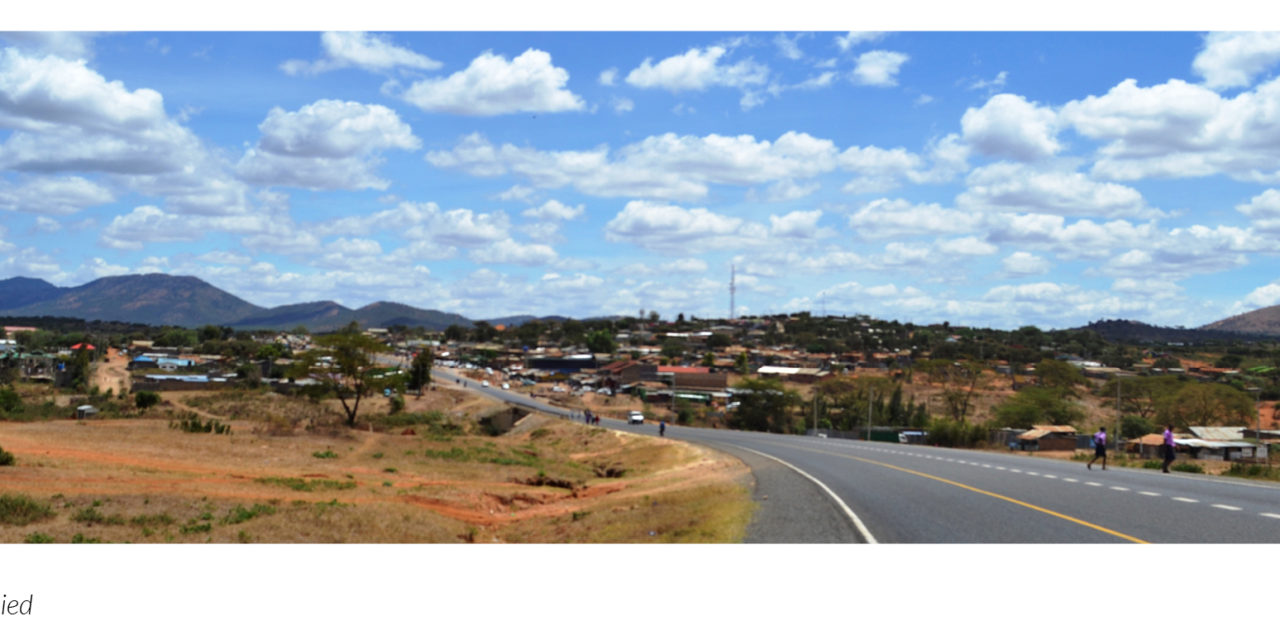

As a disguised public service vehicle driver, James* also regularly travels to Meto, a district far to the south that is close to the border with Tanzania, in order to transport charcoal produced in the district back to the capital. As mundane as this journey may seem, thanks to a ban imposed on charcoal production and trade in Kenya, James* is in fact transporting contraband goods.

A close track by the GI-TOC team on this operation, it was revealed that James* begins his journey from Nairobi at 7pm to reach Meto by midnight. The charcoal sale is arranged between James’ boss, a charcoal dealer, and a broker working in the Meto forest region. The broker ensures enough charcoal is collected from ‘bases’ of charcoal production throughout the forest to meet his dealer’s needs.

In some regions of Kenya, such as Kitui and Kajiado, local communities are sometimes intimidated into producing charcoal for dealers who control the region’s market. Investigations by GI-TOC in Kajiado, established that a cartel involving local chiefs, Kenya Forestry Service officers, police and some politicians has reportedly targeted private and communal land that is home to indigenous tree species for charcoal production. GI-TOC reported.

At sunset the following day, James* begins his return journey to the capital. The transportation of charcoal involves attempting to evade law enforcement or negotiating a series of bribes along the route. James’ boss, the dealer, uses matatu drivers like him for transportation, both because of their speed and their know-how in dealing with police.

How much a transporter pays per bribe varies, but they are able to estimate what they are likely to pay based on the quantity of their charcoal consignment.

Due to the higher risk of transporting charcoal under the ban, transporters, or dealers who control transport, push up prices to account for money paid as bribes or potential losses due to confiscation and arrests.

A charcoal dealer in Nairobi told the GI-TOC team that the increased risk of having trucks seized by the police, or of arrest, has forced transporters who are not ‘protected’ by dealers out of business. James* first drives his truck to a car wash at Ilbisil- Kajiado County, where all the dust and mud is removed, to avoid detection by traffic police on the lookout for charcoal since dusty vehicles tend to draw attention.

James* arrives in Nairobi between 3:00 am and 4:00 am EAT, just before the streets are flooded by people. His final task as a driver is to evade the city’s traffic police, before delivering his consignment to its final destination.

Despite the intentions of the charcoal moratorium, ever-increasing demand for cheap energy in urban centres and the ability of dealers and transporters to consistently evade and collude with law enforcement means that the charcoal market is still a lucrative proposition in Kenya. In James’s words, ‘after doing this for years, I have come to accept that charcoal is gold’.

In a trial held before the Chief Magistrate Court on 21st March, 2018, George Osiye was convicted of the offence of removing forest produce contrary to section 64(1) (a) as read with section 64 (2) of the Forest Conservation Management Act 2016. The particulars of the offence are that on 21st March 2018 along Namanga – Nairobi road in Kajiadio central Sub-county he was found transporting 4 bags of charcoal using motor vehicle registration KBL 373N Nissan Serena without a permit from the Director of Kenya Forest Service for the year 2018. In his own plea of guilty George Osiye was convicted and sentenced to a fine of Kshs 50,000 in default four months’ imprisonment. In addition, the magistrate forfeited the vehicle to the state.

Aside from bribes made to police along the route, James also makes payments to owners of farms passed when moving charcoal from the forest to the main highway, in order to ensure their cooperation. Informal agreements may also be formed between charcoal transporters and the police. These include what is known as kusafisha barabara, meaning ‘to cleanse the road’ in Kiswahili. GI-TOC observed.

A dealer who sources charcoal from Busia, Ilbisil and Kajiado described how this entails collusion between powerful charcoal dealers and the police service, whereby police are withdrawn from major transport routes, allowing the unimpeded flow of charcoal from place to place. If roadblocks and patrols need to be reintroduced, dealers will receive prior notice from the police involved, he told GI-TOC.

In a report by Kenya News Agency -KNA Kitui County Ecosystem Conservator Joyce Nthuku, said charcoal production is largely indiscriminate and the danger is that loggers prefer trees that take decades to mature yet there are no efforts to replenish the environment after the wanton destruction. Nthuku noted that without alternative means of livelihoods, people tend to ignore the ban and engage in illicit charcoal production and trade rather than complying with formal processes to control production or improve production methods

The charcoal market is also a key source of employment: in Kenya, the Ministry of Environment and Forestry estimated in 2016 that the charcoal trade was the largest informal-sector employer, with over 700 000 players, who in turn were believed to be supporting between 2.3 million and 2.5 million dependents.

Yet demand for charcoal has led to widespread deforestation and damage to ecosystems and biodiversity that, in turn, threatens the environment that sustains rural populations. Regulation of the charcoal market demands a difficult balancing act: the quality of life of millions of urban residents and employment in poor communities on the one hand, and the need to preserve biodiversity and reduce carbon emissions on the other.

Yet some governments in East Africa have turned to blunt instruments in order to achieve this fine balance. In Kenya, this came in the form of the nationwide moratorium on charcoal production and trade in domestically produced charcoal – although the commodity can still be legally imported –, first introduced in 2018 and still in effect today.

According to Luka Chepelion, a member of the County Executive Committee in charge of Environment and Forestry in West Pokot, north-west Kenya, ”police have also been reported actively transporting charcoal themselves. In at least one instance, a large load has been confiscated only to reportedly disappear from the inventory, likely sold to another dealer.”

Featured image: A highway cuts through the town of Ilbisil, a key trafficking centre for charcoal produced in Kajiado County. Kajiado is allegedly home to a cartel that controls charcoal production involving local chiefs, Kenya Forestry Service officers, police and some politicians. Courtesy of GI-TOC.

Recent Comments